The Value of Health

The Value of Health

As the 2012 election approaches, the health care debate rages on among candidates, businesses, and citizens. The debate centers on basic questions of who should pay for health care and what does health insurance include. But as the obesity epidemic widens, and questions over food production arise, a broader debate over the value of health is beginning to take place.

While U.S. citizens debate the structure of health care, the country is discovering a hidden cost to the overseas wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. U.S. troops return needing not only intense physical therapy for outward wounds, but also treatment to overcome inward trauma as they cope with what they have seen.

They can never know. It doesn't matter how many times you tell them. Doesn't matter how, you can draw a picture, you can make a goddamn feature film, and they, they, would never totally be able to understand exactly what you're dealing with. So to confront that you just give up. And you, you know, hide in the woods.

Ever since I was a child I was absolutely enthralled with the idea of combat and battle and war and the history of war and, you know, all the rest of that. I played more war than anybody in my neighborhood, I was always that neighborhood kid running around with the toy guns.

When I was 18 I showed up the recruiter and told him I wanted to join the infantry. And, uh, he told me I didn't want to join the infantry, multiple times. And he showed me to the Battalion Commander or whatever they had in the recruiting office and he explained to me further that I didn't want to see, that I didn't want to join the infantry because I was going to and as he banged on his desk rhythmically, he says to me that I was going to 'see some shit.'

I had a very hard time during the first couple weeks, months, maybe even year, adjusting to the fact that I was a civilian again. And then the obvious culture shock of being a college student and uh, having to deal with, you know, just 18-year-old, 19-year-old kids and walking to school every day because you know, I was living close enough to campus and I could walk and I got a little backpack on my back and I'm going to school and you know, I should have a lunch box and mommy packed it. And like, you know, it's like, fucking you know, what, seven months earlier I was, like, killing people and now it's like I'm going to school.

I like to go out and ride my motorcycle. I feel like that helps clear my head a lot because it gives me something I need to focus on and that's the only thing I can focus on or I'm gonna die. I think a lot of people around here don't even realize that there's like veterans that go to this school and stuff.

My 20th birthday was in Afghanistan. We had a night patrol that night and it was like a ten-click night patrol. So on this night patrol, and every step I'm just thinking like, man, I'm gonna get fucking blown up on my birthday. And I was just thinking that the whole time. People talk about like, oh, my birthday sucked. You know, this year, I had to work or whatever. Like really? You had to work your four hours at like, Foot Locker on your birthday? I went on a goddamn foot patrol on my 20th birthday. I could have died.

You know, in the public media today, we hear post traumatic stress disorder, and people, unless you've studied it, don't really realize the depth of the impact on the individual, on the human soul as well as, you know, our thought process, um, our behaviors, and our emotions.

When a guy dies, especially in combat, we cover the body up with whatever you got. And you know, it's just an emergency blanket or a fucking poncho or whatever else. Uh, you never get the feet. The feet generally splay to the sides. Uh, and that's all you see. You see the feet and that's kind of your last image of your buddies that you have.

When I first got home it was, it was pretty bad. Uh, actually for a while, probably about three months, I could barely even fall asleep without drinking. There's no way I could live on Court Street, because I wouldn't be able to sleep at all on the weekends.

Just from, like, people yelling. Um, that's one thing that sets me off. Especially, like, during the day, if I'm just walking somewhere and I hear someone yelling, even if they're like excited, if it's from a distance and I hear someone's yelling it instantly gets my attention and I'm kinda like, 'Oh, what the fuck is going on?' Your brain is so conditioned from that stimuli, because you've been trained for so long to react to those situations like that. Um, that, you know, things that sound like gunshots or explosions or whatever. It's really hard to turn that off.

The mythic reality of yes, we're waving our flag and this is a good cause, you start questioning that when you see the atrocities that happen in war. And you see the bad things that happen to good people. Even our language is 'We engage the target.' We aren't trained to say, you're going to shoot a boy, or you're going to shoot a woman, or you're going to shoot a human being, or you're going to murder somebody. We don't use that language in our training. Our training is mythical and we're on automatic pilot.

We were on a presence patrol in Kandahar Province in Zhari district. And uh, a motorcyclist came up through the middle of the convoy and touched himself off. Uh, blew himself, blew the bike up. Killed Reiners, killed Wittman, killed Pagan.

No, I don't think you ever leave the desert. It's like a cage that you get stuck in and then you know, you got to battle it out and then when you get out, you might physically be out but, but, mentally you're still stuck there, and you're gonna be stuck there. And it just gets to the point where you accept that, that's reality and you accept that that's the norm and you accept that that's, you know, your life. And you're never gonna get out of it. Like I said, you accept the fact that you're gonna die and that's just the way it is. And you don't know when, but you accept the fact that you're gonna die and you write the stupid letter to your parents and all the people that you love and care about and you know, you just accept that's the last thing you're ever gonna say to them. And that's hard. That's a hell of a hump to get over.

That's probably the hardest thing you do in the entire, you know, time that you're in the infantry. But once you've gone past that point and you've accepted that I'm dead, then you're good. But you're only good for there. Because when you don't die and you come back, then you gotta live with the fact that you're not dead. And a lot of your buddies are. Uh, you have to confront the fact that a part of you, you left there with them. Because they didn't get to come home. Alive. Uh, and you know that there's, you know, a part of you that stayed there when they died. And it's never gonna leave.

Dear mom. The world is so much different here, sometimes I feel as if I'm just living in a really bad dream. Things that would seem unimaginably unbearable back in the States become commonplace here. We have no way to watch television here but knowing American media, I'm sure you've already. . .

I do remember when he came back from Iraq the first time, um, it was kinda sad because he was sitting at the kitchen table once and he just started crying and that was not like Eric.

He was here near the 4th of July. We walked around the neighborhood and then coming back, one of the, um, boys that he used to play with apparently set off a big firecracker, M-80 or something of that category. And it just stopped Eric in his tracks. It was just like you had hit him with a ball bat. It just stopped him.

You feel alone all the time. You understand, you come to an acknowledgement that no one else around you has any idea what you're dealing with. They don't have a clue. And uh, for a while you're angry about that. You're really bitter about the fact that all these mother-fuckers don't have any idea what, you know, I'm dealing with. And you know, you're sitting in line in Subway and this douchebag in front of you is bitching because you put too much mayonnaise on a sandwich or something. And you're like, dude, you don't know what problems are. Like, you know, nobody in this place is wounded seriously or dead or you know, nobody's life just changed because they put too much fucking mayonnaise on your sandwich.

I don't really wanna say that I have PTSD, even though I've been diagnosed by the VA, because it, just because of that huge social stigma that goes along with it. What a lot of people don't know about the VA is that it sucks. Um, so they diagnosed me with PTSD or whatever and then, which this kinda shocked me, is that they haven't really followed up on it at all, and this is almost a year ago now. But all they did when I went there was just throw drugs at me. And I was like, well I guess I'll have to figure this out on my own.

PTSD is too simplistic in its definition. It's listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as an anxiety disorder. That's the category that it's under: anxiety disorders. Anxiety is only one piece of that. It is more in depth and more comprehensive in what it does to the human spirit.

We are not ready for the numbers of veterans coming back from war, to reintegrate them into our communities. We really need to train our mental health professionals to, um, understand and recognize the cause of the symptoms that our veterans, especially, but other domestic violence and all the other trauma victims have, is the direct result of the trauma itself, and you have to treat that trauma and you have to treat the whole person, um, with several different, uh, interventions. Where we get into trouble I think is, we treat those symptoms with medications. We sedate people, and we don't get at the root cause, which is the trauma itself.

You got to, you know, continue moving. Yeah, they might be dead, but you're still alive. And that's, that's the key. That's why you always have to keep in mind in combat is that you have to keep breathing. You have to keep moving. And even if you're shot, you know, you have to continue moving. And that's, uh, that's the lesson.

That's the lesson in life, is that you have to keep moving. Combat brings out the most fundamental primal lessons of life that you won't get any other way and people can tell you that shit when you're a little kid, they can tell you it, you know, while you're growing up a million times, and it never really sticks until it's life or death. And you realize that this is really what I have to do if I'm going to continue existing on earth. I have to keep moving.

Veterans are not the only U.S. citizens voicing concerns over health care. Access to health care, particularly insurance, can be limited by income. The hidden costs of healthy living go beyond trips to the doctor, however. A low income often denies families’ access to knowledge about healthy lifestyles, and fresh foods and produce can quickly put a hefty dent in small budgets.

Being [a veteran] myself, I think that when they write that check, that blank check for anything and everything, including their life, I think they should receive a blank check when they get back.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, passed by President Barack Obama in March 2010, involves sweeping changes to the current healthcare system in the United States. Included in the law, a mandate that will require individuals to have health insurance or pay a penalty, beginning in 2014. The U.S. Supreme Court will review the law later this year and decide whether or not it is constitutional for Congress to regulate states and individuals at a federal level. Across partisan boundaries, most Americans have strong opinions about the state of health care and ramifications of potential policy changes.

“Health insurance goes a long way, if a person starts feeling healthier, then they can eat better, or they can sleep better, and that’s really important.”

Jonathan Story, 28

Athens, Ohio

“Its too expensive and they don’t wanna waste their money on it, cause a lot of people don even bother going to the hospital so why would they pay for health insurance? When they don’t even wanna go?”

Travis Roush, 20

Gallipolis, Ohio

Patricia Robey, 67

Nelsonville, Ohio

"Since I'm retired, I get [health care] through Social Security and so forth. … But I haven't had to use mine for a while, so I'm glad."

Dana Moffet, 41

Nelsonville, Ohio

"[Health care] runs me about $75 a month. And minimum wage, two people, yeah, that's quite a chunk of change."

Andrew Kaczor, 22

Athens, Ohio

"I think having health insurance is not a right, as a citizen. It's more of a privilege."

William Johnson, 81

The Plains, Ohio

"I'm a registered Democrat. The only reason I'm a Democrat is because my father was."

Jeremy Cornett, 40

Cheshire, Ohio

"I believe it should be a right, but I can understand how some could see it as a privilege."

I had my first heart attack in 2007, then my last heart attack was in 2011. When you don't have nothing and your health is bad and you don't have nobody to turn to, and you've got to go somewhere and they won't see you at the hospital, because you don't have insurance, I know what that is first hand.

It's hard for a man of my age, sixty years old, to get a good job with any benefits or anything like that. I left a job making $42,000 a year to nothing. I didn't have no money to pay for the hospital bills or nothing like that, so I had to file bankruptcy on them.

The first hospital bill I paid myself, it cost me $10,000 out of my pocket. But I didn't have a job, it took all my life savings I had, took everything I had. You could say why didn't God save your home out there. I don't know why. But I know that I live for the Lord, and he said he'd take care of my needs and I needed a home, I needed insurance, but I didn't have any, he provided me a clinic to go to.

We see anywhere from twenty-five to forty-nine, that's the most we've ever seen is forty-nine, and usually it averages out between twenty-five and thirty-five. So we are strictly for people who have no insurance whatsoever. And we have a lot of people like that in Gallia County. And they have to be Gallia County residents.

I was so sick when I went there the first time, and I wanted to make sure I got there before the crowd, so I went two hours early and set before they opened up.

How tall are you sir?

About six foot. How much now?

140, 198.

The impression that I had was that all citizens here in the United States have access to medical care and basic health care. Much to my surprise there is a good percentage of the entire population of the United States are uninsured, which is, to me, very significant.

Last night, I had fries, and a couple hot dogs, and big old pickles.

It is, how much, it is 283 the normal is 120.

Whoo! 160 more huh? Wow.

What will happen is, if your sugar goes high, it will affect your kidney, it will affect your heart, and it will affect your eyes. Ok. Ok. And you have enough trouble. Alright. Right? Right.

The medical community and the public health community have know for a long time that we have a huge segment of population in this -- let's say tri-state area, which is the upper part of Appalachia -- that do not have medical care coverage. No type of insurance, either not offered or they cannot afford it. If it is offered it's astronomical and they can't afford it. It takes out of their take home pay so they just don't carry it.

It's too high. They want $50 a week for the insurance on me, and they want $100 a week for my wife. That's $150 a week, with the salary I get, I make $500 a week. Take $150 off that, and I'm just doing nothing but working and paying insurance. By the time I pay all my other bills and things, you wouldn't have nothing; you wouldn't have no money for groceries. So I don't have no health insurance, I can't afford that. I don't make the greatest wages, but I'm making a wage for this area to sustain you. But you go out there and buy insurance, you can't afford it.

Cardiac disease is rampant in this area. Smoking is right up there with it, and so you have problems with lung cancer, cardiac disease, stroke, hypertension, and by the time we see them, they're up in their 50s, maybe 60s, and then you've got long term chronic problems that could have been taken care of and fixed years before that time. So when you look at it from a public health standpoint, we're failing miserably. We really are.

There is a growing population that has abandoned processed foods and joined a more whole, sustainable food movement. In Athens, Ohio, personal relationships form every day between local farmers, distributors, restaurant owners, and consumers. These unique food communities contribute to the good health of their members and the local economy.

The choices that lead to a healthy lifestyle are often made in the early stages of life. Studies show breastfeeding strengthens immune systems and can be the first line of defense against obesity. As different groups push for healthy childhoods, the debate over women’s health care in general has become a flashpoint for the larger discourse concerning insurance, the options available to women, and just exactly what medications and services should be guaranteed to patients.

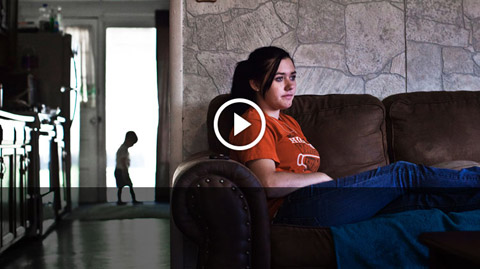

Like, I don't try to fit in but I just don't fit in. I can't really explain how different I am. I just feel like I watch more what I do, and I think before I do stuff but they don't. Normal teenagers aren't supposed to, but I do, I think. When I got pregnant, I felt ashamed.

I don't think I got scared until it all set in and I had to tell people. I never thought I would have an abortion. It wasn't right for me. And some people brought up adoption but if I touched my belly he would kick back like he was touching me. I could just imagine when he was older, I guess playing like that. I knew that I wanted to keep him.

It was a little hard for us at first but we kind of arranged mine and my husband's schedule, that way we could help take care of Braylen while she goes to school.

I don't want him to struggle with what I've experienced. It's very exhausting. It's a lot of fun, too, but if I ever had a free day, I would just sleep. My mom always offers, "Do you want me to take him for two, three hours?" And I'll try to lay in here and I just can't. I can't sleep, because I'm wondering what he's doing.

I don't know if there's such a thing but she's addicted to Braylen. I really do.

School's hard with him. He don't make it hard; I'm not blaming it on him.

It's just, like at night he goes to sleep about 11:30 and then I get up at six o'clock and go all day again until about 11:30 at night, again. They always say children of teen moms are more likely to be abused or go to prison and teen moms abandon their babies, but I'm not going to. Me and Braylen aren't going to be a statistic.